Canadian Pandemic Influenza Preparedness: Planning Guidance for the Health Sector (CPIP) is a federal, provincial, and territorial (FPT) guidance document that outlines how jurisdictions will work together to ensure a coordinated and consistent health-sector approach to pandemic preparedness and response. CPIP consists of a main body, which outlines overarching principles, concepts, and shared objectives, as well as a series of technical annexes that provide operational advice and technical guidance, along with tools and checklists on specific elements of pandemic planning. The CPIP main body and its annexes are intended to be used together.

CPIP was first published in 2004. In 2006, the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network (PHN) Council approved an updated version of CPIP as an evergreen document to be updated as required. In 2009, Canada’s pandemic preparedness planning efforts were tested for the first time, with the emergence of the H1N1 influenza pandemic. In 2012, a CPIP renewal process was initiated by the PHN Council. This latest version of CPIP, was approved by FPT Deputy Ministers of Health 2014, with further update in 2018. It incorporates evidence from H1N1 lessons learned reviews conducted at the FPT and international levels and by various stakeholder groups, and scientific advances. As an evergreen document, the CPIP main body and each annex will be reviewed every 5 years, with updates made between review cycles, if necessary.

Since 2012, The CPIP Task Group (CPIP TG) has overseen the CPIP renewal process.The CPIP TG consists of members with expertise in the areas of pandemic and seasonal influenza, pandemic preparedness planning and response, emergency management, epidemiology, public health, virology, bioethics, immunization, surveillance, and laboratory diagnosis.

The updated CPIP allows for a more flexible and adaptable response to future pandemics, providing scope for provinces and territories (PT) to adapt their own plans and responses to local and regional circumstances. The title of the document also has changed, from Canadian Pandemic Influenza Plan for the Health Sector to Canadian Pandemic Influenza Preparedness: Planning Guidance for the Health Sector, to more accurately reflect its role and intended use as a guidance document.

CPIP now supports a risk-management approach and includes new concepts such as pandemic impact assessment, descriptions of pandemic scenarios of varying impact, and identification of triggers for a Canadian response. It also better reflects Canada’s geographic, demographic, cultural, and socio-economic diversity and the imperative for planners to take this diversity into account. CPIP has been subject to extensive FPT government review and targeted stakeholder consultations. Stakeholders included national-level organizations representing health professionals, emergency preparedness and first responders, community services, the private sector, and Indigenous peoples.

Canadian Pandemic Influenza Preparedness: Planning Guidance for the Health Sector (CPIP) provides planning guidance to prepare for and respond to an influenza pandemic. Influenza pandemics (subsequently referred to as pandemics) are unpredictable but recurring events that occur when a novel influenza virus strain emerges, spreads widely and causes a worldwide epidemic. Unfortunately, it is not possible to predict the anticipated impact of the next pandemic or when it will occur.

Planning for a prolonged and widespread health emergency of unpredictable impact is challenging but essential. It requires a “whole of society” response and the coordinated efforts of all levels of government in collaboration with their stakeholders.

Pandemic planning activities within the health sector in Canada began in 1983. The first Canadian pandemic plan was completed in 1988 and was followed by several updates. In 2004, the Canadian Pandemic Influenza Plan for the Health Sector was published as the result of extensive collaboration among FPT and other stakeholders. Before this version, the last major update to the CPIP and its annexes occurred in 2006.

The 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic (subsequently referred to as the 2009 pandemic) provided the first real test of Canada’s pandemic preparedness planning efforts. Collaboration among all levels of government and stakeholders was unprecedented compared with previous events like the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003. The public health and health care systems were stressed but in most instances were able to cope. Antiviral stockpiles were deployed and pandemic vaccine was administered to millions of Canadians. There were, however, many challenges identified in this experience.

Canada’s pandemic planning continues to evolve on the basis of research, emerging evidence and the lessons learned from the 2009 pandemic. The value of building on seasonal influenza surveillance systems and control measures is well recognized. Making these systems and measures as robust as possible in the interpandemic period will help prepare for a strong pandemic response.

CPIP’s overall purpose is to provide planning guidance for the health sector for pan-Canadian preparedness and response, in order to achieve Canada’s pandemic goals:

First, to minimize serious illness and overall deaths, and second to minimize societal disruption among Canadians as a result of an influenza pandemic.

The main body of CPIP provides strategic guidance and a framework for pandemic preparedness and response, whereas the CPIP annexes provide operational advice and technical guidance, along with tools and checklists. As an evergreen document, CPIP will be updated as required to reflect new evidence and best practices.

It is important to note that CPIP is not an actual response plan. Rather, it is a guidance document for pandemic influenza that can be used to support an FPT all-hazards health emergency response approach. While CPIP is specific to pandemic influenza, much of its guidance is also applicable to other public health emergencies.

CPIP is pan-Canadian pandemic planning guidance for the health sector developed under the guidance of a group of Canadian experts. The primary audiences are the FPT ministries of health together with other ministries that have health responsibilities. While it is anticipated that CPIP’s strategic direction and guidance will inform FPT planning in order to support a consistent and coordinated response across jurisdictions, PTs have ultimate responsibility for planning and decision-making within their respective jurisdictions. CPIP also serves as a reference document for other government departments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) engaged in health issues, and other stakeholders.

While CPIP provides pandemic planning guidance, it does not address business continuity preparedness or overall management of a health emergency. These activities are critical for an effective pandemic response; however they are more appropriately addressed in the emergency plans of individual jurisdictions and organizations. Neither does CPIP address pandemic preparedness and response in the non-health sectors (e.g., community and social services, public safety), although some of its content may be a useful reference.

There have been considerable changes to CPIP since the 2006 version in both format and content.The strategic nature of the information in the main body of the planning guidance has been strengthened and lessons learned from the 2009 pandemic have been incorporated. While the overall pandemic goals remain the same, new objectives have been added along with a set of principles to support the response. These are accompanied by a discussion of ethical considerations pertaining to pandemic preparedness and response, and consideration of the implications of Canada’s diversity and the needs of vulnerable persons. Roles and responsibilities for each level of government have been described more explicitly.

The new CPIP outlines a risk management approach to support a flexible and proportionate response. Risk management involves setting the best course of action in an uncertain environment by identifying, assessing, acting on and communicating risks. Information has been added about what is known and what is uncertain about pandemic influenza. The planning assumptions have been updated, and four hypothetical planning scenarios have been developed to illustrate the importance of developing plans and response strategies that are flexible and can be adapted as circumstances require. CPIP also provides triggers for action that are based on novel virus emergence and pandemic activity in Canada rather than the global World Health Organization (WHO) phases. Finally, content has been updated in each of the specific response areas.

The CPIP technical annexes are being renamed according to their subject (e.g., Surveillance, Vaccine) instead of being named alphabetically. As part of the CPIP renewal process, it is intended that each of the technical annexes will be revised.

While there are four types of influenza virus (A, B, C and D), only influenza A and B viruses cause seasonal outbreaks in humans, and only influenza A viruses have been known to cause pandemics. Aquatic birds are the natural hosts for influenza A viruses, although a wide range of species can be infected and significant disease outbreaks can occur in poultry, pigs and other species. Most of these animal influenza virus strains do not cause disease in humans although occasional human (zoonotic) infections occur, usually through close contact with infected poultry or animals.

Influenza pandemics or worldwide epidemics occur when an influenza A virus to which most humans have little or no immunity acquires the ability to cause sustained human-to-human transmission leading to community-wide outbreaks. Such a virus has the potential to spread rapidly worldwide, causing a pandemic. Footnote 1

These novel viruses may arise through genetic reassortment (a process in which animal and human influenza genes mix together) or genetic mutation (when genes in an animal virus change, allowing the virus to easily infect humans). Pigs can become infected with influenza viruses from different species and act as a “mixing vessel” to facilitate the reassortment of genes from different viruses.

Not all novel influenza viruses evolve into pandemic viruses. Some novel subtypes, like the avian A (H5N1) virus, have caused sporadic human cases on an ongoing basis since 1997 but have not gained the ability to spread easily in humans. As the overall human case fatality rate for A (H5N1) infections has been over 50%, Footnote 2 there are concerns about the potential of a high impact human pandemic if this virus gains the capacity to spread easily between people.

Historical evidence suggests that influenza pandemics occur three to four times per century. In the last 100 years there were four pandemics separated by intervals of 11 to 41 years. They varied greatly in their impact, as measured by illness and deaths. The 1918-1919 pandemic had a high impact, killing an estimated 30,000 to 50,000 people in Canada and 20 to 50 million people worldwide. The impact of the 1957 and 1968 pandemics was considered moderate, whereas the 2009 pandemic had a lower impact.

| 1918-1919: | H1N1 “Spanish flu” |

|---|---|

| 1957-1958: | H2N2 “Asian flu” |

| 1968-1969: | H3N2 “Hong Kong flu” |

| 2009: | H1N1 "Influenza A(H1N1) 2009" |

While every pandemic is different, some common characteristics can be recognized:

During the 1918-1919 pandemic, 99% of influenza-associated deaths in the United States (US) were in persons under 65 years of age and nearly half of these among previously healthy adults 20-40 years of age. In subsequent pandemics, the proportion of influenza-associated deaths in the US in persons under 65 years of age was 36% (1957-58), and 48% (1968-69). Footnote 4 In the 2009 pandemic 70% of reported deaths in Canada were in persons under 65 years of age. Footnote 5

The term “severity” is often used to describe both severity of disease in individuals (clinical severity) and the overall “severity” of a pandemic in a population. In CPIP, the term severity is used to describe clinical severity of disease in individuals and impact is used to describe the effects of a pandemic on the population.For planning and response purposes, describing the “impact” of a pandemic on the population is a more meaningful approach than talking about its “severity”. It is acknowledged that this usage may vary from the approach of some other authorities. For example, the WHO uses the term “pandemic severity” for what CPIP terms “impact” but the concepts are the same. Footnote 6

Severity refers to clinical severity of disease in an individual (e.g., mild, moderate or severe disease).

Impact refers to the effects of a pandemic on a population (e.g., low, moderate, or high impact).

Pandemics vary in their impact, as do seasonal influenza outbreaks, although usually on a higher scale of magnitude. A low impact pandemic might resemble moderate to severe seasonal influenza outbreaks, although its epidemiological profile would be different in important ways as previously described. In contrast, pandemics of moderate to high impact could result in high rates of illness and death across the country and would severely challenge the health care sector. They could also disrupt the normal functioning of society and put people with limited resources and support systems into a more vulnerable state.

Numerous factors can affect pandemic impact. These are outlined below and described in more detail in Appendix A:

The impacts of a pandemic in psychosocial terms may be acute in the short term but can also undermine the long-term psychological well-being of the population. Psychosocial issues are not only experienced by those who become ill; distress permeates through the family and the community (e.g. financial stress due to economic downturns, caregiver burnout, occupational stresses, stigma/social exclusion).

The range of issues associated with psychosocial planning is broad involving all levels of government and multiple planning partners, including humanitarian actors such as community-based organizations, government authorities and NGOs and are closely aligned with the practice of risk communication Footnote 7 .

Influenza is unpredictable - every influenza season and every pandemic is different. These uncertainties make pandemic planning challenging and highlight the need for flexibility and adaptability. Some of the major unknown areas about the next pandemic are the following:

There were many important epidemiological observations from the 2009 pandemic to take into account in future planning and response. These include the speed with which cases and sporadic outbreaks appeared in Canada after the novel virus was first detected and the early involvement of some remote and isolated communities, with severe disease in some First Nations communities. There was considerable variation in the timing and intensity of pandemic waves, especially the first wave, across the country. Although the symptoms were similar, age groups affected and risk conditions varied from seasonal influenza. Greater impact was seen in pregnant women and Indigenous peoples, and persons with morbid obesity were newly recognized as being at high risk for complications. For the duration of the pandemic, seasonal influenza strains were replaced by the pandemic strain and as with previous pandemics, it was not certain whether this single A strain dominance would continue in the 2010/2011 influenza season, A (H3N2) and B strains began to re-circulate and the pandemic virus became the seasonal A (H1N1) strain.

A number of challenges were identified in the national response. Surveillance demands were very heavy from the start, and were accentuated by the lack of linked information systems in some jurisdictions, unclear protocols for sharing information, and limited capacity for epidemiological analysis. The process for release of the National Antiviral Stockpile (NAS) was uncertain. There was high demand for critical care and ventilators for affected children and adults. Preparation and timely approval of concise national guidelines was difficult. The pandemic immunization program faced challenges with uncertain timelines for vaccine delivery, prioritization of vaccine supply, logistics of local campaigns and communication of changing recommendations.

On the positive side, previous planning processes and relationship-building led to unprecedented FPT collaboration and many successful stakeholder engagement efforts. Existing surveillance systems, like FluWatch, and ready-to-use hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette campaigns were valuable. Mathematical modeling was successfully used to support decision-making in some areas (e.g., recommendations for vaccine prioritization) and it was recognized that a number of other areas would benefit from modeling (e.g. predicting pandemic impact).

Following the pandemic, the Government of Canada (GC) Footnote 9 and most PT governments conducted lessons learned reviews. In addition, the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology held extensive hearings on the response. Footnote 10 Some common themes emerging from these reports and recommendations were identified to improve preparedness, such as:

Canada’s geographic features and population diversity can create challenges in mounting an effective response to a public health emergency. Canada is a huge country geographically with communities that range in size from large cities to small rural and remote settlements. The proportion of people living in rural areas in Canada (18.9%) is low in comparison to other developed countries and is steadily declining. The proportion of the rural population, however, varies greatly (from 14% to 53%) from one province or territory to another. It is lowest in British Columbia and Ontario and is highest in the Atlantic provinces and the territories. Footnote 11

Canada is diverse in terms of language, religious beliefs, ethnicity, culture and lifestyle. Canada’s Indigenous peoples make up almost 4% of the population, the second highest percentage in the world after New Zealand. Footnote 12 While many Indigenous peoples live in remote and isolated communities in the North, about half live in urban areas. The median age of Canada's Indigenous peoples is considerably younger than that of non-Indigenous peoples (27 years compared with 40 years respectively). Footnote 13

The proportion of foreign-born people in Canada is one of the highest in the world at 20%, Footnote 14 most of whom settle in large cities. Toronto and Vancouver now have over 40% visible minority populations and Montreal has 16%. Footnote 15 In addition there are many temporary residents, such as foreign workers and foreign students.

The needs of remote and isolated communities may be greater than other communities because of geographic isolation and health, social, environmental, economic and cultural considerations. These may affect the baseline health status and thus increase the vulnerability of their residents. In addition, some remote and isolated communities lack basic amenities, such as household access to running water, that are assumed to be present when public guidance like hand hygiene is issued. It is important to consider these factors, along with limited access to health care and transportation challenges, when planning for all aspects of the pandemic response in remote and isolated communities. Similar concerns may affect urban marginalized or vulnerable populations.

There are individuals within all jurisdictions whose needs are not fully addressed by traditional services or who cannot comfortably or safely access and use standard resources. Examples of these vulnerable persons include, but are not limited to, individuals who are:

It may not be a single one of these conditions that determines the degree of vulnerability, but rather a combination of them under certain circumstances Footnote 17 .

Studies indicate that there is a social gradient of risk during influenza pandemics, based on social vulnerabilities that are likely to lead to increased exposure to infection, risk of basic human needs not being met, insufficient support and/or inadequate treatment. Footnote 18 Vulnerable populations might become more marginalized if pandemic health services are streamlined into standard approaches to reach the general population.

Within the nationally coordinated pandemic response it is important to allow sufficient local flexibility to address the unique needs of vulnerable populations. Detailed influenza-specific planning guidance has been developed for vulnerable populations in Canada. Footnote 19, Footnote 20 These referenced documents should be useful for FPT and regional/local planners.

Responsibility for planning for vulnerable populations is often unclear and although public health is typically involved, inclusion of all relevant stakeholders is important for comprehensive planning and buy-in. It is important for planners to address the unique needs of their jurisdiction. This begins with identifying populations and settings associated with increased risk of illness or severe outcomes from pandemic influenza along with persons who might need tailored prevention and care services during a pandemic. Specific planning considerations include information needs (e.g., language, cultural style and methods of dissemination); access to assessment, treatment (including antiviral medications) and convalescence support; access to vaccine; and need for support for activities of daily living.

This section summarizes the more important ethical considerations in pandemic planning but is not intended to be an actual ethical framework. Ethical considerations are also addressed more specifically in various CPIP annexes with supporting tools and frameworks where available.

In Canada, ethical considerations are increasingly taken into account in the development of health policy. Ethical analysis helps to identify the ethical issues and determine how to do the right thing in a fair, just and transparent way. Many of the issues encountered in pandemic preparedness and response involve balancing rights, interests and values. Examples include decisions over resource allocation; prioritization guidelines for pandemic vaccine and antiviral medications; adoption of public health measures that may restrict personal freedom; roles and obligations of HCWs and persons providing medical first response, as well as their employers; the potential need for triage in the provision of critical care; and responsibilities to the global community. Footnote 21

The application of ethical reasoning to pandemic preparedness and response begins with identifying and prioritizing the ethical questions in the issue under consideration. Analysis should include reflection on the ethical considerations associated with the options, taking into account the societal versus individual interests and values that are at stake. Ethical tensions are inevitable. When weighing the options, it is important to be guided by the Canadian pandemic goals.

As pandemic planning initiatives fall within the domain of public health, they are guided by a code of ethics that is distinct from traditional clinical ethics. Footnote 22 Whereas clinical ethics focuses on the health and interests of individuals, public health ethics focuses on the health and interests of a population. When a health risk like a pandemic affects a population, public health ethics predominates, and a higher value is placed on collective interests.

In practical terms, this means there should be an emphasis placed on trust and solidarity. Successful public health activities require relationship-building and can contribute to creating and maintaining trust between individuals, populations and health authorities. Solidarity is the notion that we are all part of a greater whole, whether an organization, a community, nation or the globe. Another important consideration is reciprocity, meaning that those who face disproportionate burdens in their duty to protect the public (e.g., HCWs and other workers who are functioning in a health care capacity, for example police or fire personnel who are providing medical first response) are supported by society, and that to the extent possible those burdens are minimized.

The concept of stewardship is also closely related to trust. Stewardship refers to the responsible planning and management of something entrusted to one’s care, along with making decisions responsibly and acting with integrity and accountability. Trust, stewardship and the proper building of relationships also mean that the power conferred to government and health authorities will not be abused. For example, if restrictions are deemed essential for proper risk management, they must be effective and proportional to the threat, meaning that they should be imposed only to the extent necessary to prevent foreseeable harm. These restrictions should also be counterbalanced with supports to minimize the burden on those individuals affected.

The concepts of equity and fairness are very important to Canadians. In a pandemic context, they lead to a number of considerations. As much as possible, benefits and risks should be fairly distributed through the population. This may be difficult, however, in some circumstances, such as a pandemic that differentially affects certain populations or a very severe pandemic if resources are in short supply. Decisions should take health inequities into account and try to minimize them, rather than make them worse. Access to necessary health care may be restricted in a health crisis; however, available resources (e.g., vaccine and antiviral medications) should be distributed in a fair and equitable way. What will constitute fair and equitable distribution will be context dependent. Therefore the transparency and reasonableness of decision-making processes are important.

Good decision-making processes are also essential for ethical decision-making. They involve the following: Footnote 23, Footnote 24

The legal considerations that arise in the context of pandemic preparedness and response are varied and complex. International laws as well as FPT legislation will be relied upon during both the preparedness and responses phases of a pandemic.

International Health Regulations (2005)

The current International Health Regulations (2005) [IHR (2005)] came into force in 2007. They provide a framework for monitoring and enhancing global public health capacity and international communication regarding potential public health emergencies of international concern (PHEIC). The aim of the IHR (2005) is to prevent the international spread of disease while limiting interference with international traffic and trade. The IHR (2005) also establish a more effective and transparent process for WHO and its Member States (including Canada) who are States Parties to the Regulations, to follow when determining and responding to a PHEIC. Most importantly, they broaden the scope of international collaboration to include any existing, re-emerging or new disease that could represent an international threat.

The IHR (2005) include obligations for States Parties to:

In order for Canada to meet the IHR (2005) requirements, all levels of government must collaborate. In Canada, PTs use established protocols to report influenza infections of international concern to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), which is Canada’s NFP. After an initial assessment if notification is required, PHAC communicates with the WHO. Reportable influenza-related events include cases of human influenza caused by a new subtype as well as cases having potential international public health implications that meet the notification criteria established under Annex 2 of the IHR (2005). WHO then re-assesses the event to determine whether the event constitutes an actual PHEIC. The first PHEIC declared by the WHO under the IHR (2005) was the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in 2009.

Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework

The Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework (PIP Framework) for the sharing of influenza viruses and access to vaccines and other benefits was adopted by the World Health Assembly in 2011. The PIP Framework aims to improve the sharing of influenza viruses with pandemic potential and to achieve more predictable, efficient and equitable access for countries in need of life-saving vaccines and medicines during future pandemics.

Under the Framework, Member States, including Canada, are responsible for:

The Emergency Management Act (2007), section 6(1), makes each minister accountable to Parliament for a government institution responsible to identify the risks that are within or related to his or her area of responsibility and prepare emergency management and response plans with respect to those risks; to maintain, test and implement those plans; and to conduct exercises and training in relation to them.

In accordance with responsibilities under the Act, the federal Minister of Health is primarily responsible for developing, testing and maintaining mandate-specific emergency plans for the federal Health Portfolio, which includes Health Canada (HC) and PHAC. These emergency plans outline the federal response to national public health threats or events such as major disease outbreaks (including an influenza pandemic), and to the health effects of natural disasters or major chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear and explosive (CBRNE) events.

Furthermore, the Quarantine Act (2005) strives to prevent the introduction and spread of communicable diseases into and out of Canada by providing the Minister of Health with the authority, including enforcement mechanisms, to take public health measures as required. Pandemic Influenza Type A is listed in the Act’s Schedule of Diseases.

Health emergency management in the PTs in Canada is governed by legislation specific to each jurisdiction. This legislation requires the PT governments to have comprehensive emergency plans respecting preparation for, response to and recovery from emergencies and disasters, including those with potential impact on critical infrastructure. Important health emergency management powers are also found in public health legislation.

The 2009 pandemic provided an opportunity to identify problems or gaps in existing legislation (including public health legislation) that should be addressed in order to respond more effectively to a future pandemic. An effective response requires an authority to establish appropriate leadership for a coordinated response, along with authority for PT and local public health officials to implement appropriate control measures. Planners should ensure that they will have authority to mount an effective response whether or not an emergency is officially declared.

Goals serve an important purpose in guiding preparedness and response, and in prioritizing the use of resources if necessary. Canada's goals for pandemic preparedness and response are:

First, to minimize serious illness and overall deaths, and second to minimize societal disruption among Canadians as a result of an influenza pandemic.

These national goals were originally presented in the Canadian Pandemic Influenza Plan for the Health Sector, which was endorsed by FPT Ministers of Health in 2004. The goals, and their sequence, had undergone extensive deliberation by FPT pandemic planners and other stakeholders. A survey carried out as part of the Canadian Program of Research on Ethics in a Pandemic (CanPREP) found that over 90% of participants agreed that the most important goal of pandemic influenza preparations was saving lives. Footnote 25 During the 2009 pandemic, the pandemic goals were invaluable in guiding aspects of the response.

The supporting objectives for the health sector are as follows:

The following principles underpin Canadian pandemic preparedness and response activities and decision-making:

In addition to these main guiding principles, Canadian pandemic planning and response activities are also guided by:

The global nature of a pandemic requires a response that differs from many other types of emergency. Traditionally, the responsibility to deal with an emergency is placed first on the individual/household to manage the effects of the emergency as it affects them, and then on successive levels of government as the resources and expertise of each are needed. Public Safety Canada is responsible for coordinating the whole of government response when the federal government is involved in the response to an emergency. Within the PTs a similar function is performed by the appropriate ministry or emergency measures organization.

In a pandemic situation, a pan-Canadian whole-of-government response is required so that all potential resources can be applied to minimizing the pandemic's negative health, social and economic impacts. Pandemic plans should be aligned across jurisdictions to facilitate successful FPT collaboration during a pandemic.

The following sections provide a high-level overview of FPT health emergency planning and response relevant to pandemics.

The GC has in place a coordinated system of federal emergency management frameworks, systems and emergency response plans, many of which can be accessed at Public Safety Canada's web site. These plans are based on the four components of the emergency management continuum (prevention and mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery) and they use an all-hazards approach. Emergency response plans for the federal Health Portfolio are part of this GC system.

The FPT health sector also has a system of frameworks and emergency response plans parallel to those of the federal health sector, that are comprehensive and flexible enough to address any type of national health emergency. The development and maintenance of some of these documents, including CPIP, is overseen by the PHN.

The federal and FPT emergency management plans are supported by various operational annexes and guidance documents. These are nested under the generic all-hazards emergency response plans and deal with more specific threats.

Because a pandemic is a significant health event, the FPT ministries of health have the primary mandate for the health sector response in their respective jurisdiction and act as advisor for other sectors on health issues.

At the federal level, the Centre for Emergency Preparedness and Response (CEPR) at PHAC is the Health Portfolio's focal point for coordinating and providing a wide range of emergency management services with other federal departments, PT governments, NGOs and the private sector. CEPR is responsible for the Health Portfolio Operations Centre (HPOC) in Ottawa and its linkages to other operational centres at the FPT level.

Coordination of the FPT health sector response to a pandemic will follow the governance structure outlined in the FPT Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events (FPT-PHRPBE). The FPT-PHRPBE is complementary to and used in conjunction with existing jurisdictional planning and response systems.

The FPT-PHRPBE is intended to bridge the gap between PT public health response plans and federal health response plans by providing a single, common overarching governance framework for the FPT health sector that can be applied, in full or in part, during a significant public health event requiring a coordinated FPT response, such as an influenza pandemic.

The FPT-PHRPBE defines a flexible FPT governance mechanism that identifies escalation considerations and response levels for a scalable response, and to improve effective engagement amongst public health, health care delivery and health emergency management authorities during a coordinated FPT response. This will ensure that at the time of a response, notification processes and inter-jurisdictional information-sharing will be enhanced; public and professional communication will be addressed; and advance planning and decision-making between and amongst multiple jurisdictions will be facilitated.

Finally, as the effects of a pandemic are not exclusive to the health system, it is critical for FPT governments and emergency management partners to use a common approach in responding to a pandemic. Emergency social services (e.g. non-medical services considered essential for the immediate physical and social well-being of people affected by disasters) should be coordinated within the broader PT response and aligned with health system activities.

The North American Plan for Animal and Pandemic Influenza (NAPAPI) outlines how Canada, Mexico and the US intend to work together to combat an outbreak of animal influenza or an influenza pandemic in North America. The NAPAPI addresses both animal and public health issues, including early notification and surveillance, joint outbreak investigation, epidemiology, laboratory practices, medical countermeasures (e.g., vaccine and antiviral medications), personnel sharing and public health measures. It also addresses border and transportation issues. While the NAPAPI is not legally binding, it reflects strong commitments by the countries involved to work collaboratively.

Collaboration in pandemic planning and response is strengthened by having clearly defined and well-understood roles and responsibilities. While this section focuses on government responsibilities, it is acknowledged that other partners also have important roles and responsibilities in a pandemic. These partners include the non-health sector, private sector, NGOs, municipalities and local/regional health authorities, and international organizations. Similarly, members of the general public bear responsibility for keeping themselves informed and for cooperating with measures to reduce the spread of illness.

WHO's pandemic roles and responsibilities are outlined in the WHO pandemic influenza risk management guidance document and include: Footnote 27

Responsibility for health services in Canada is shared across all levels of government. High-level roles and responsibilities for FPT governments are outlined below; more detailed information about roles and responsibilities for specific response components can be found in the CPIP annexes. It is recognized that responsibilities for federal populations, which are summarized at the end of this section, are complex and evolving.

A. International aspects

International aspects of influenza management and liaison are a federal responsibility.

The federal government is responsible for:

B. Collaboration, communication, information sharing and policy recommendations

While PT governments are responsible for communications plans and messaging within their jurisdictions, a coordinated pan-Canadian pandemic response requires collective infrastructures, response capacities and coordinated activities.

The federal government is responsible for:

FPT governments will work collaboratively to:

C. Antiviral medications and influenza vaccine

The federal government is responsible for:

PT governments are responsible for maintenance, monitoring, distribution and administration of antiviral medications and vaccine in their respective jurisdictions. They will work collaboratively to:

The PT governments are also responsible for the distribution of vaccines and antiviral medications to most federal populations, but this varies by federal population and jurisdiction (see section F on federal populations).

FPT governments will work collaboratively to develop strategies to mitigate the effects of insufficient or delayed antiviral drug and/or vaccine supply, should such a situation arise.

D. Health sector preparedness and response

Health sector preparedness and response remains the responsibility of each jurisdiction. In some jurisdictions responsibility for emergency social services also falls to the health sector.

PT governments are responsible for:

The federal government has similar responsibilities for federal departments within the health sector and for federal populations in collaboration with the PTs (see section F on federal populations).

E. Health care provision

The provision of health care is an essential component of pandemic response and is primarily a PT responsibility.

PT governments are responsible for:

The federal government is responsible for:

F. Federal populations

Federal populations are those populations for which the federal government either provides health care and benefits, goods and/or services or reimburses the cost of providing health care and benefits. With the exception of the Canadian Forces which has its own distinct health care system for active members, the needs of federal populations must be integrated into PT pandemic planning activities in order to establish a comprehensive and coordinated pandemic response.

Federal populations include the following:

The federal government is responsible for:

The federal government will work collaboratively with PT governments to:

Risk management is a systematic approach to setting the best course of action in an uncertain environment by identifying, assessing, acting on and communicating risks. A risk management approach provides a useful framework for addressing the uncertainties inherent in pandemic planning and response. Risk management supports the CPIP planning principles of evidence-informed decision-making, proportionality, and flexibility; and a precautionary/protective approach when there is uncertainty early in an event.

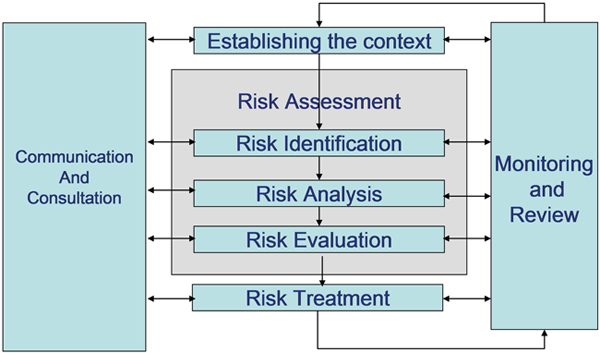

Figure 1 provides a graphic overview of the risk management process as outlined in ISO 31000, the international standard for risk management. The individual steps involved in risk management are then briefly described.

Risk assessment is a central component of risk management. Its purpose is to provide evidence-informed information and analyses for making informed decisions on how to treat particular risks and select between options. There are three parts to risk assessment:

Risk treatment follows risk assessment and involves identifying and recommending risk treatment options, i.e. options for management or control. Risk treatment options should include steps that need to be taken in advance, as well as potential actions at the time of the pandemic.

Communication and consultation are also integral parts of the risk management process. Effective communication with stakeholders should facilitate adequate understanding of the risk management decision-making process, ensure that the process is transparent and help people to make informed decisions. A risk communications plan should be developed at an early stage.

Monitoring and review are important for assessing factors that could change over time and for documenting effectiveness of interventions. Such reviews should lead to periodic updates of the risk assessment.

Given the large number of variables that are involved in influenza pandemic planning, comprehensive risk management is challenging. The four pandemic planning scenarios described in section 3.7 can assist with risk identification by providing a starting point to think through the risks that would be associated with pandemics of varying impact and their implications.

It is also worthwhile to anticipate key decisions that will need to be taken during the pandemic to help guide the development and analysis of options. It is also worthwhile to clarify ahead of time and to the extent possible what level(s) of government should be involved with which types of decision when the time comes. Examples of these key decisions are as follows:

Anticipating key decisions should be accompanied by identification of the types and sources of information required for decision-making. Establishing robust surveillance for seasonal influenza establishes baselines, develops capacity and provides a platform for escalation during the pandemic.

Anticipating key decisions should also lead to development of relevant options for risk treatment. From a pandemic preparedness perspective, examples of risk treatment include continuity of operations planning; establishment of stockpiles for antiviral medications and other key supplies; development of advance contracts for pandemic vaccine; strengthening influenza surveillance systems, diagnostic and analytical capacity; establishment of protocols for pandemic research; and establishment of communications networks to plan effective and coordinated risk communications strategies.

When a pandemic occurs, planning scenarios are replaced by a real event and response activities will be guided by the available evidence. During the initial stages, little may be known about the likely pandemic impact or the populations most at risk. Many decisions will have to be made before solid information is available and then adjusted, if necessary, as more becomes known, keeping in mind that it is often difficult to scale back a response. As the evidence emerges over time, understanding of the situation will continue to change as new information becomes available and will always be incomplete. A risk management approach will be used throughout the response by all responders. Risk assessments will provide key input into FPT decision-making by identifying what is known at that point in time, what might occur and when, and the major areas of uncertainty.

PHAC will facilitate development of timely and credible risk assessments to support FPT decision-making. These formal risk assessments will be conducted at the start of the pandemic to inform the initial response and then periodically as new information emerges (e.g., at the end of a pandemic wave). Risk assessments will address key information needs, including viral characteristics, the anticipated or experienced impact on the health care system and community, age and risk groups most affected, occurrence of antiviral resistance and estimated effectiveness of control measures. As the pandemic progresses, there will be questions about likely occurrence of more pandemic waves, whether new risk factors are emerging and whether the response should be escalated or de-escalated. Appendix B identifies relevant considerations for initial and ongoing pandemic risk assessments and identifies potential sources for the supporting information.

This section on planning assumptions and section 3.7 on pandemic planning scenarios describe two important tools for pandemic planning. These tools provide distinct but complementary approaches.

Identifying planning assumptions is a way to deal with uncertainty. Assumptions provide a useful framework for planning but should not be regarded as predictions. While planning assumptions are rooted in evidence to the extent possible, Footnote 29, Footnote 30 they are basically educated guesses. As the pandemic unfolds, emerging evidence is used to guide the response. Informing the planning assumptions identified below is the WHO's Pandemic influenza risk management interim guidance (2013), the UK's Scientific summary of pandemic influenza & its mitigation (2011) and discussions from the Canadian Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Planning Assumptions Workshop held in 2011.

This section discusses another important tool for pandemic planning. The use of multiple planning scenarios is specifically intended to support the planning principles of evidence-informed decision-making, proportionality, and flexibility; and a precautionary/protective approach.

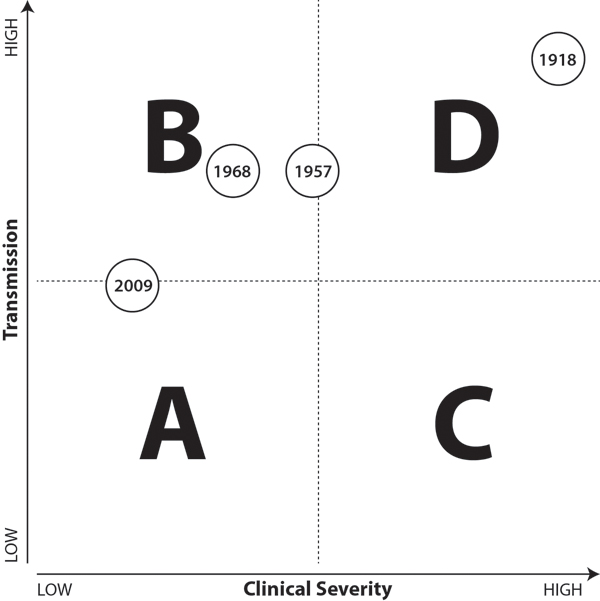

Planning scenarios provide a starting point to think through the implications and risks that would be associated with pandemics of varying population impact. Scenarios can also be used for exercises and training in support of pandemic plans. To help with risk identification, four pandemic planning scenarios have been developed that describe potential pandemic impacts varying from low to high. Figure 2 displays the four scenarios in a two-by-two table and estimates where the past four pandemics might be placed, according to an analysis conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Footnote 32

Scenario A (low impact) - this scenario involves an influenza virus with low transmissibility (ability to spread) and low virulence (clinical severity). Its impact is comparable to that of moderate to severe seasonal influenza outbreaks or the 2009 pandemic. It might be expected to stress health care services.

Scenario B (moderate impact) - this scenario involves an influenza virus with high transmissibility and low virulence. Its impact is worse than seasonal influenza in terms of numbers ill, which would be expected to stress health care services through sheer volume. High absenteeism would put all sectors and services under pressure.

Scenario C (moderate impact) - this scenario involves an influenza virus with low transmissibility and high virulence. Its impact is worse than seasonal influenza outbreaks in terms of severe clinical illness, which would be expected to stress critical care health services. The high virulence could cause significant public concern and may lead to people staying home from school and work.

Scenario D (high impact) - this scenario involves an influenza virus with high transmissibility and high virulence, and its anticipated impact is much worse than that of seasonal influenza outbreaks. It would cause severe stress on health care services, and high absenteeism would put all sectors and services under extreme pressure.

There are several important points to note about the scenarios:

Table 1 provides some added description to the scenarios for planning purposes, along with potential impact considerations associated with each scenario.

Initial period when impact is unknown - A formal scenario has not been proposed for the initial period when the pandemic has not yet been characterized in terms of its potential impact. However, some of the possible observations for this preliminary period are as follows:

Pandemic phases were introduced into pandemic plans to assist planning and serve as triggers for action, thus supporting the principles of flexibility and proportionate response. Previous Canadian pandemic plans incorporated the WHO pandemic phases, with additional designations proposed to identify activity levels within Canada.

After the 2009 pandemic, the IHR Review Committee Footnote 35 recognized that the WHO pandemic phases had presented challenges in interpretation and were used in different ways - as a planning tool, as a method to describe the global situation and/or as an operational tool to trigger action. The Committee recommended simplifying the WHO phase structure and separating operational considerations at country level from the WHO global preparedness plan and its phases.

WHO's 2013 pandemic guidance Footnote 36 describes the four phases that WHO will use to communicate a high-level global view of the evolving picture. The phases reflect WHO's risk assessment of the global situation regarding each influenza virus with pandemic potential that is infecting humans. The four global phases are:

The global phases and their application in risk management are distinct from (1) the determination of a PHEIC under the IHR (2005) and (2) the declaration of a pandemic. These are based upon specific assessments and can be used for communication of the need for collective global action, or by regulatory bodies and/or for legal or contractual agreements, should they be based on a determination of a PHEIC or on a pandemic declaration. Footnote 37

As pandemic viruses emerge, countries face different risks at different times and should therefore rely on their own risk assessments, informed by the global phases, to guide their actions. The uncoupling of national actions from global phases is necessary since the global risk assessment, by definition, will not represent the situation in each country.

Canada's response to the novel/pandemic virus will relate to its presence and activity levels in this country, which may not coincide with the global picture. Therefore, the WHO global phases will not be used to describe the situation in Canada or be used as triggers for action in Canadian jurisdictions. While the triggers for action described below may parallel some of the global WHO phases, it is not expected that they will line up exactly. For example, Canada might be well into the first pandemic wave before WHO announces the global pandemic phase (as happened in the 2009 pandemic) or conversely Canada might be still anticipating the first domestic outbreaks when the pandemic phase announcement is made.

In the 2009 pandemic, there was considerable variation in pandemic wave activity across Canada and even within PTs, in terms of both timing and intensity. This was particularly apparent in the first wave making blanket descriptions, triggers or responses inappropriate.

Describing pandemic activity

Descriptive terms such as the start, peak and end of a pandemic wave, will be used instead of phase terminology to describe pandemic activity in the country or in a jurisdiction within Canada. Pandemic wave activity can be further characterized for jurisdictions of any size using FluWatch definitions for no activity, sporadic activity, localized activity and widespread activity. Footnote 38

Triggers for action

Triggers for action provide guidance for initiation of FPT activities and for their modification and cessation. Pandemic response should be appropriate to the local situation, so it is important that triggers and related actions be applied at PT or regional/local level as appropriate to the situation. Potential triggers for action in Canadian jurisdictions during the initial alert stages and the pandemic itself are identified in Table 2. The typical actions listed are at a high level; more detailed triggers for individual response components can be found in the annexes. Note that the triggers are not necessarily linear; for example, not all jurisdictions may find their capacity exceeded and therefore some may not need to invoke that particular trigger.

This chapter provides a high-level overview of the major components of influenza preparedness and response. Each section of the chapter describes the purpose and strategic approach of one of the response components and demonstrates how it supports the overall pandemic goals. Detailed operational guidance and tools for each component can be found in the respective CPIP annex.

All parts of the health sector, including public health, will be under stress during a pandemic. Advance planning, training and exercises will greatly assist in handling this increased demand on health services, staffing, resources and supplies and in providing the best possible clinical outcomes for persons ill with influenza. Continuity of operations and surge capacity planning are key components of health sector preparation, together with strong infection prevention and control and occupational health programs within each organization that provides health services.

Public health authorities play a leadership role in their jurisdiction in pandemic preparedness, response and recovery. They are responsible for communication to the public, the health sector and other stakeholders. The public health response to a pandemic also includes surveillance (both epidemiological and laboratory), the provision of pandemic vaccine and antiviral medications, and the application of public health measures such as promotion of personal and social distancing measures to reduce spread in households and the community.

In planning for the delivery of health services, it is important to encompass the entire continuum of care from medical first response to critical care, and to include community health partners. Planning for the provision of health care needs to be linked with public health and community-wide partners so that interdependencies can be identified and addressed.

The health care system includes workers of many disciplines, who will be at varying levels of risk during an influenza pandemic. HCWs are defined broadly as individuals who provide health care or support services in the health care setting, such as nurses, physicians, dentists, nurse practitioners, paramedics, medical laboratory workers, other health professionals, temporary workers from agencies, unregulated health care providers, students, volunteers and workers who provide support services (e.g., food, laundry, housekeeping). The concepts and advice that are provided for HCWs also apply to other workers who are functioning in a health care capacity, for example police or fire personnel who are providing medical first response.

The purpose of pandemic surveillance is to provide decision-makers with the timely information they need for an effective response. Pandemic surveillance uses data obtained through routine and enhanced surveillance activities (e.g., data from sources such as laboratories, PT partners, hospital networks and sentinel practitioners) together with information from special studies to obtain a comprehensive and timely epidemiological picture of the pandemic.

These pandemic surveillance programs will monitor parameters such as:

Strategic approach

A risk management approach to an influenza pandemic requires access to timely information, analysed and presented in a way that is useful to decision-makers. Epidemiological and laboratory surveillance data are key components of the formal risk assessments that will be produced to inform the response. One of the most critical needs is an early assessment of the potential impact of the pandemic so as to prepare the health care system and to plan interventions that are proportional to the situation. Systems or studies to produce the early impact assessment and other required information need to be in place before the pandemic.

Pandemic surveillance should be built on existing surveillance systems for seasonal influenza, which involve an extensive network of surveillance partners and are practised every year.

During a pandemic, collection of additional surveillance elements may be required to identify risk factors for severe disease and populations at increased risk. Targeted surveillance activities may be required for remote and isolated communities, including many Indigenous communities, to describe outbreaks appropriately in these regions. Other special studies (e.g., seroprevalence surveys) will be needed to inform decision-making.

Surveillance activities will need to be adapted in response to rapidly evolving situations; they may be streamlined, expanded or scaled down depending on information needs at particular times within the evolving pandemic. The scope of the pandemic and the urgency of information needs will require expedited and secure electronic data transfer and enhanced capacity for data analysis and interpretation.

More details about pandemic surveillance strategies and activities can be found in the Surveillance Annex.

Laboratory-based surveillance is an integral part of monitoring influenza activity. Because the signs and symptoms of influenza are similar to those caused by other respiratory pathogens, laboratory testing must be conducted to diagnose influenza definitively. Rapid identification of a novel influenza virus and timely tracking of virus activity throughout the duration of the pandemic are critical to the success of a pandemic response. In the early stages of a pandemic, laboratory services also contribute to appropriate clinical treatment.

The purpose of laboratory services during a pandemic is to:

Strategic approach

The pandemic laboratory response is built on the principles of collaboration, flexibility and use of established practices and systems. As part of annual influenza surveillance, all public health laboratories and other laboratories that routinely test for influenza submit aggregate data weekly during the influenza season to the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML). These data are collated and disseminated by PHAC through the Respiratory Virus Detection Surveillance System and FluWatch. In addition, public health laboratories and other designated laboratories across the country submit isolates to the NML to monitor for antigenic changes within the circulating viruses. This information is shared with international partners through GISRS. Sustaining these relationships and strengthening capacity within the laboratory system during the interpandemic period will support a timely and effective pandemic response.

During a pandemic, influenza testing laboratories will support epidemiological efforts to track the spread and trends of the pandemic, monitor antiviral resistance and support clinical management. The Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network (CPHLN) will support public health and diagnostic laboratories by providing recommendations and best practices for specimen collection and testing for the novel influenza virus. The NML will share protocols, reagents and proficiency panels to ensure that test methods are capable of detecting the new virus. Molecular testing is the primary method used for the diagnosis of influenza.

Antiviral resistance will be monitored and outcomes will inform clinical management of patients. Antiviral resistance testing is conducted primarily at the NML, as well as some provincial laboratories.

The laboratory response will be adjusted as the pandemic progresses. Initially the NML will be heavily engaged in characterization of the novel virus and development of diagnostic reagents. All laboratories should anticipate high test volumes initially as the novel virus spreads across the country. During peak periods, laboratories will need to prioritize specimen collection to prevent overload. At this point, diagnosis of influenza in the community will be made primarily by clinical assessment; however, testing to support the management of certain patients (e.g., those requiring admission to hospital) will be expected to continue together with identification of outbreaks and surveillance. If ongoing monitoring shows increasing levels of antiviral resistance, more testing may be necessary to support clinical management of severely ill patients, especially those not responding to treatment.

Throughout the pandemic, public health, diagnostic and research laboratories, including those involved in the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN), will also play an important role in supporting studies to better understand the novel pandemic virus and its impact.

More details about pandemic laboratory strategies and activities can be found in the Laboratory Annex.

Public health measures are non-pharmaceutical interventions that can be taken by individuals and communities to help prevent, control or mitigate pandemic influenza. Public health measures range from actions taken by individuals (e.g., hand hygiene, self-isolation) to actions taken in community settings and workplaces (e.g., increased cleaning of common surfaces) to those that require extensive community preparation (e.g., pro-active school closures). The purpose of public health measures is to:

Strategic approach

Public health measures are typically implemented at the community level. The responsibility and legislative authority for implementing public health measures belong to the relevant PT and local public health authorities, with the exception of international border and travel related issues for which the federal government is responsible. In addition, the Canadian Forces Health Services is responsible for implementing public health measures on all Canadian Forces establishments/bases/wings/stations across Canada and for Canadian Forces personnel deployed abroad.

There are important concepts to consider when planning and implementing public health measures. The measures should be used in combination to provide “multi-layered protection”, as the effectiveness of each measure on its own may be limited. Actions should be tailored to the anticipated pandemic impact and the local situation, supporting the principles of flexibility and proportionality. Some measures, like hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette, are applicable in all pandemics. Other measures (e.g., proactive school closures and travel restrictions) might be used only in moderate- to high-impact situations, as they can be associated with significant societal and economic costs.

A risk management approach will help weigh the potential advantages of particular interventions against their disadvantages and unintended consequences. Decisions about which measures to deploy also raise fundamental ethical challenges. For example, when considering restrictive measures, it is important to balance respect for autonomy against protection of overall population health. In such situations, the principles of proportionality, reciprocity and flexibility are involved, with a view to safeguarding individual freedom to the extent possible while promoting protection against the health and societal consequences of influenza infection.

There are several types of public health measures for jurisdictions to consider during an influenza pandemic:

While aggressive measures (e.g., widespread antiviral use and restriction of movement) to attempt to contain or slow an emerging pandemic in its earliest stages were previously considered possible on the basis of modeling, experience from the 2009 pandemic has resulted in general agreement that such attempts are impractical, if not impossible.

Additional details about public health measures can be found in the Public Health Measures Annex.

Immunization of susceptible individuals is the most effective way to prevent disease and death from influenza. The purpose of Canada’s pandemic vaccine strategy is to:

The phrase “vaccine for all Canadians” is intended to be interpreted broadly. It refers to all persons in Canada (whether or not they are citizens) as well as Canada-Based Staff (CBS), their dependents and Locally Engaged Staff (LES) at Canadian missions abroad and Canadian active duty personnel (Canadian Forces) abroad.

An effective pandemic vaccine strategy is built on strong seasonal influenza immunization programs. The overall impact of the pandemic vaccine strategy will depend on vaccine efficacy and uptake, as well as the timing of vaccine availability in relation to pandemic activity. Using current egg-based vaccine production technology, pandemic vaccine production is expected to take from four to six months, so it is not likely to be available by the time the first pandemic wave reaches Canada. Furthermore, it will become available in stages, which may require prioritization of initial vaccine doses.

Strategic approach

In 2011, Canada entered into a new ten-year contract for pandemic influenza vaccine supply to ensure that there is rapid and priority access to a supply of adjuvanted pandemic influenza vaccine produced in Canada. Canada’s pandemic vaccine strategy also includes contracting for a secondary supply of a pandemic vaccine.

Health Canada has developed a regulatory strategy to review and authorize a safe and efficacious pandemic vaccine for use in Canada within the shortest time frame possible. A pan-Canadian approach to pandemic immunization, including prioritization of populations during initial roll-out of the vaccine, will help optimize equitable access and desirable outcomes. Pan-Canadian guidance will include an allocation plan for equitable vaccine distribution, recommendations for pandemic vaccine use and recommendations for prioritization of initial supplies.

Other key elements of the national vaccine strategy include the monitoring of vaccine uptake, adverse events and vaccine effectiveness, building on existing systems such as the Canadian Adverse Events Following Immunization Surveillance System (CAEFISS). Rapid studies will be carried out to confirm or refute vaccine safety concerns.

PTs, Canadian Forces Health Services, and federal departments with the responsibility for immunization should have plans for efficient and timely vaccine administration, including the ability to target key population groups and collect information on vaccine uptake and adverse events. Lessons learned from the 2009 pandemic indicate that vaccine registries and electronic information systems to capture and transmit data are essential tools to support the vaccine program.

More details about the pandemic vaccine program can be found in the Vaccine Annex, including a prioritization framework to guide decision-making if vaccine is expected to be in short supply.

Antiviral medications can be used to treat influenza cases or to prevent influenza in exposed persons (prophylaxis). Antiviral medications are the only specific anti-influenza intervention available that can be used from the start of the pandemic, when vaccine is not yet available.

Canada’s antiviral strategy supports FPT stockpiles of antiviral medications for use in the event of an influenza pandemic, primarily for early treatment and for outbreak control in closed facilities. Early treatment of influenza cases, as early as possible within 48 hours of symptom onset, is recommended in order to reduce the severity and duration of illness, particularly the occurrence of influenza-related complications, hospitalization and death. Early treatment may also help mitigate societal disruption by reducing the duration and severity of illness experienced by workers in the health care and other critical infrastructure sectors.

Strategic approach

There are two national stockpiles in Canada:

Federal government departments, such as the Canadian Forces (for active duty personnel) and Global Affairs Canada (for mission staff overseas), hold stockpiles of antiviral medications to meet the anticipated needs of their staff.

Jurisdictions need strategies to facilitate timely access to antiviral medications, particularly for high-risk persons including pregnant women, children (who need special formulations), vulnerable populations, and residents of remote and isolated communities. Pre-positioning of antiviral medications should be considered for some communities to facilitate rapid access (e.g., remote northern communities).

Clinical guidelines have been developed for antiviral use for seasonal influenza. Footnote 39 Virus-specific clinical guidance and treatment protocols will need to be developed at the onset of the pandemic, based on pandemic epidemiology and available scientific evidence. Pandemic use will focus primarily on early treatment of influenza cases, particularly persons with severe disease or with risk factors for complications or severe disease. There are limited indications for the use of antiviral medications for prophylaxis during a pandemic, primarily for control of laboratory-confirmed influenza outbreaks in closed health care facilities and other closed facilities or settings where persons at high-risk of complications reside.

Distribution and uptake of antiviral medications should be monitored in real time to optimize appropriate use, identify the need for additional purchases during the pandemic, and support post-pandemic utilization and effectiveness studies. Monitoring adverse reactions and antiviral resistance helps inform decision-makers as to whether changes in the recommendations regarding antiviral use are required. Adverse reaction reports are collected and assessed through the Canada Vigilance Program of the Marketed Health Products Directorate (MHPD) of Health Canada. Ongoing monitoring of antiviral resistance is conducted by the public health laboratory system and reported as part of FluWatch.

More details about antiviral medications and their use in a pandemic can be found in the Antiviral Annex, including a prioritization framework to guide decision-making if antiviral medications are expected to be in short supply.

A major influenza outbreak may have a substantial impact on the ability of health care organizations to keep those providing or receiving health care services safe. Infection prevention and control (IPC) and occupational health (OH) programs should work together to prevent exposure to and transmission of pandemic influenza during the provision of health care. Working jointly with occupational health and safety committees is essential in meeting these goals. The application of appropriate IPC and OH processes by HCWs and organizations is important in all health care settings along the continuum of care, including but not limited to medical first response, practitioners’ offices and other ambulatory care settings, acute care, long-term care and home care settings.

Strategic approach

A timely pandemic response is only possible when an organization and its personnel are experienced in IPC and OH protocols and practices, supported by strong programs. Well-functioning IPC programs should prevent, limit or control the acquisition of health care associated infections for everyone in the health care setting, including patients, HCWs, visitors and contractors. Well-functioning OH programs should identify workplace hazards and support appropriate processes and training to ensure that employees can perform their duties in an environment that minimizes exposure to environmental hazards.

Important elements of IPC and OH programs for pandemic preparedness and response in the health care setting include the following:

For detailed guidance about IPC and OH activities during a pandemic, see the annex on Prevention and Control of Influenza during a Pandemic for all Healthcare Settings.

The effective provision of health care provides patients with the right level of care in the right place, at the right time. In a pandemic this means managing an influx of patients with influenza, while maintaining care required for patients with urgent non-influenza conditions. It is necessary for any organization that provides health care to plan for a range of scenarios, including those with very high patient load and potential high staff absenteeism, as demand for health care services may exceed the capacity of the existing system. At the start of a pandemic, early assessment of its anticipated impact will help the health care sector to implement plans to manage the anticipated workload.

Strategic approach

Planning for the delivery of health care in a pandemic is a particular challenge as there is little excess capacity in the Canadian health care system, particularly in remote and isolated communities. Nonetheless surge capacity planning is an essential component of pandemic preparedness for all levels of care, including telephone information lines, primary and ambulatory care practitioners, emergency medical services, hospital and critical care, long-term and palliative care, home care and other community care including death care services (funeral homes, medical examiners, coroners). Surge capacity planning involves development of strategies for enhancing levels of staff and volunteers, equipment and supplies and, potentially, space to accommodate more patients. It also includes consideration of novel approaches to enhancing assessment and care. Surge capacity plans should include regional or even province-wide components.

The 2009 pandemic highlighted the importance of improving integration and coordination so that the health care response functions as a system during an emergency. This involves integration across the continuum of care within a health region and across and among PTs. Integration is facilitated by involving stakeholders from all levels of care in planning and exercises, including emergency medical services, community service providers, volunteer organizations and public health. Electronic information management systems are essential tools for monitoring service delivery and resource utilization across the health care system and transferring information among organizations.

The collection of health care delivery data is an important aspect of seasonal and pandemic influenza surveillance. Monitoring hospital and ICU admissions and ventilator use were added surveillance components in the 2009 pandemic, contributing valuable information on the epidemiology of severe disease and its risk factors. Surveillance of emergency department utilization can indicate when community health services are at or reaching capacity so that other measures can be considered.

Best practices and lessons learned advise that health care organizations and practitioners carry out business continuity planning and maintain strategic reserves of critical equipment and supplies. Detailed plans to store, distribute and track use of stockpiled items should be developed and exercised.

Pandemic-specific issues for health care provision include the following:

During a severe pandemic, death care services may be overwhelmed and local planners may need to consider alternate systems and resources than those that normally manage deaths, such as setting up temporary morgues and delaying funerals/burials. This may cause increased stress or complications in the grieving process for families, particularly when certain religious and/or cultural practices have specific directives about how bodies are managed after death. Planning guidance is available from the WHO, Pan American Health Organization and the International Red Cross on the effective management of mass fatalities during a disaster Footnote 40 .

Clinical care involves the assessment and treatment of persons with suspected or confirmed pandemic influenza. The spectrum of illness seen with influenza is broad and ranges from asymptomatic infection to severe illness causing death, which is frequently due to exacerbation of an underlying chronic condition or secondary bacterial pneumonia. Certain aspects of pandemic influenza management may be unfamiliar to some practitioners, and new risk factors and presentations may emerge. Critically ill patients may require extraordinary support measures, some of which may not be universally available in a high-impact pandemic.

Strategic approach